Leadership is a key part of making process safety work. In some ways, it is the most important part. It may also be the most difficult part. Although the science used in process safety can sometimes seem overwhelming, there is usually a third-party who can be hired to explain it. But leadership cannot be delegated to a contractor – you must do it yourself.

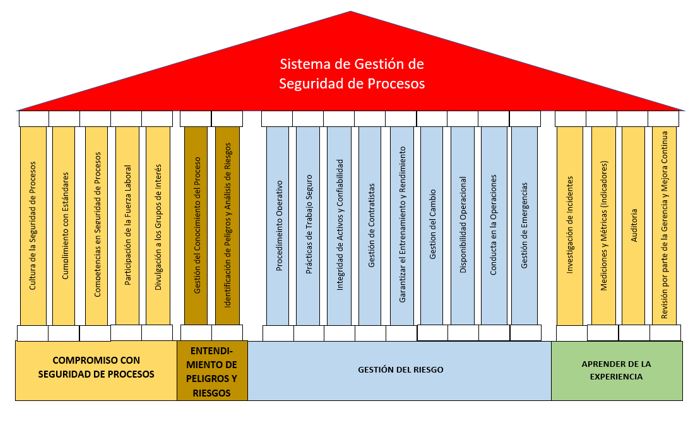

CCPS has a management system called “Risk Based Process Safety.” This management system gives us a model, which is a way of organizing all the ideas and concepts needed to successfully manage process safety in any situation. The figure below is a graphical representation of this model. When many people see this model, their first reaction is, “This is much too complicated for me and my operation.” If you feel this way, I would like to reassure you that it is not as complicated as it looks. It is likely that you are already managing about half of the items on this figure.

To understand this diagram, let’s start at the bottom, at the base of the structure. Here you see four foundations: Commitment, Understanding, Management, and Learning from experience. In any industrial operation that handles hazardous materials and energies, it is critical to understand what the hazards and risks are. Once these are understood, it is important to manage them appropriately. And since our management is imperfect, it is important to learn from our mistakes so we can improve our management systems.

But none of these things is going to happen without a strong commitment by the leaders of an organization. The leaders are those who control the resources, such as money, time, and organizational focus. If the leadership does not really want to improve process safety, it will not happen. That is why the foundation Commitment may be the most important part of process safety.

There are many ways that the leaders of an organization can show commitment to process safety. These are represented by the five “elements” constructed on this foundation of Commitment. The first is Process Safety Culture. This article will focus on this element and the role of leadership in making it successful.

CCPS offers several possible definitions of Process Safety Culture.

● “the combination of group values and behaviors that determine the manner in which process safety is managed.”

● “How we do things around here.”

● “What we expect here.”

● “How we behave when no one is watching.”

Each of these definitions includes the concept of human behavior. We are probably all familiar with the idea that human behavior is important to safety because it is a key part of Industrial Safety. The actions of a worker can have a big impact on his or her safety such as following operating procedures, wearing protective equipment.

In the same way, the behavior of leadership of an organization has a big impact on the safety of everyone. The leadership creates the context in which each person decides what they will do. This context includes the “rules” by which behavior is judged, the things that the organization values as important, and what the expectations are. This context, or culture, influences most of the activity in a company.

One example is the attitude toward money. If the leadership is always saying “we don´t have money for that” when faced with a process safety issue, then the organizational value ends up being “We can be safe as long as it doesn’t cost too much.” This can result in many decisions that affect process safety:

● Contract administrators may select the contractor with the lowest cost, even when they do not have the capabilities to do the job well.

● Engineering personnel designing equipment may not follow industry standards because they think that leadership will not accept the extra cost of doing so.

● Operations managers may continue to run the process when it is not safe to do so because they think that their leadership will not approve a plant shutdown for safety reasons.

● HSE managers investigating an accident may not recommend the significant changes required to prevent the next accident because they think that leadership will find them “excessive.”

If leadership wants to reduce the risk of catastrophic accidents, then one of the first things they should do is to work to establish a strong process safety culture. CCPS mentions several essential features to doing this:

Establish Process Safety as a core value. Many organizations do not even know what process safety is. So, the first step is likely just helping the organization understand what process safety is and how it applies to each person. This will probably require formal training, short email communications, and informal discussions over the course of several months.

Once people know what process safety is, it is time to show that it is important enough to spend money and time on. Leadership can show their value for process safety by designating a portion of the capital budget to projects designed to reduce the risk of catastrophic accidents.

Provide Strong Leadership. Leaders show the way. They provide a vision. They talk about it every chance they get. They have the same attitude toward process safety whether they are in a formal meeting or in a private conversation. Leaders do not let problems stop them, rather they look for solutions. To make process safety work, someone needs to be making the way so everyone else can follow.

Establish and enforce high standards of performance. This can be done by adopting a standard and making it clear that the standard will be followed. An example could be how the plant manages change. A leader committed to process safety will set a standard that all changes to hazardous processes must be formally reviewed before they can be implemented. The leader can check every so often if changes are being reviewed. If he finds a change that has not been reviewed, he will call the organization to account for it and insist that it be reviewed before it is implemented.

Maintain a sense of vulnerability. Most manufacturing operations have a narrative that things are done the right way, and when they are done the right way it is safe. But reality is not quite so clear-cut. Every activity involving hazardous materials and energies carries a certain amount of risk with it. Even when things are done “right”, there is still a small probability that accidents can occur. A good process safety culture will recognize and embrace this. When leadership consistently stresses the vulnerability of the operation, it helps everyone to be more diligent about the maintaining the lines of defense.

Defer to expertise. Leaders must make decisions regarding all aspects of a business. Sometimes these decisions require input from technical specialists. And sometimes the technical specialist recommends something expensive or disruptive to the organization. The leader has the power to ignore such recommendations, but this can be a dangerous path to take. Most leaders do not have technical expertise on all aspects of a business. Expertise is often required to both understand the hazards and to control the risks. When a leader refuses to defer to expertise, it not only increases the risk of the decision being taken, it also sets a precedent that the leader’s opinion is more important than expert input. This can lead to less expertise being offered to the leader in the future.

Empower individuals to successfully fulfill their safety responsibilities. Leaders can show their support for process safety by empowering the people who work for them. This means letting them make decisions that may be unpopular. One example of this is the operation of a plant. The operator, supervisor, and operations manager can each be in a situation where they know that the operation is unsafe and should be shut down to prevent a catastrophic accident. What they do depends on how empowered they feel by their leadership. If they know that the leadership will support them, they will likely shut down the plant and deal with the safety issue. If they do not, they will let the plant run and let the leader make the decision. If the leader cannot be reached, the plant can run in an unsafe condition for hours or days. A leader who values process safety will make sure that everyone knows that they are empowered to do what it necessary to keep the plant safe.

Ensure open and effective communication. Leaders can benefit from everyone in their organization if they are willing to listen to opposing viewpoints. But if the leadership punishes dissent, most people will not tell the leadership about problems. And they will certainly not suggest unpopular solutions.

Provide a timely response to process safety issues and concerns. When leadership tells the organization that they want to promote process safety, the best way they can show it is to address process safety issues that are on people’s minds today. An example is a hazard analysis that identifies several areas of improvement. If the action items take years to implement, people will not believe that the leadership is committed to safety. However, quick resolution of an issue encourages everyone to suggest even more improvements.

No matter where you are in an organization, you can be a leader to help make these things happen. But those who are in the positions of highest authority have the greater responsibility. The risk of catastrophic accidents in your plant in the next 50 years depends mostly on these leaders and the decisions they make to lead their organizations to change.

Lee el mismo artículo en español: Artículo – Liderazgo y Cultura de Seguridad de Procesos

Lee el mismo artículo en portugés: Artigo – Liderança e cultura de segurança de processos